Australian Curriculum V9.0 Key Ideas Part 1

1. Patterns,order and organisation

What’s important is that the Key ideas and the understanding

that sits beneath them are equally relevant to students who want to go on and

work in science as it is for those who want to live with an appreciation of

science. They are incredibly unifying and equitable.

What they are:

The key ideas distil down scientific knowledge into six

guiding principles that we can use to explain a diversity of scientific phenomena.

The key ideas are designed to :

• provide

lenses by which we can make sense of the world,

• support

teachers and students to make connections across the 3 strands of science,

• support

the coherence of science understanding within and across year levels throughout

Reception to Year 10.

What they are not:

Whilst big ideas help to frame the ultimate goals of science

education, it’s important to recognise that big ideas cannot be taught

directly.

If we try to devise activities that teach big ideas

directly, we end up with some superficial activity.

We don’t teach students directly about each key idea but

provide opportunities for them to learn how there are key ideas underpinning

the science concepts found within each strand ->sub strand -> content

description

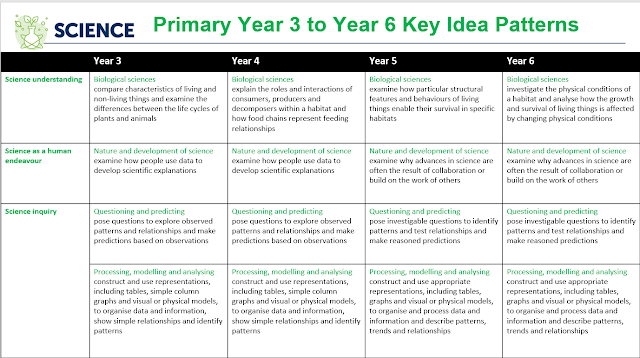

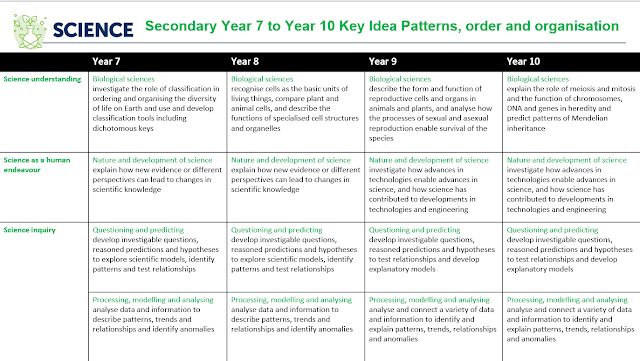

Key Idea: Patterns, order and organisation

• An

important aspect of science is recognising patterns in the world around us and ordering

and organising phenomena at different scales.

• As

students progress from Foundation to Year 10, they build skills and

understanding that will help them to observe and describe patterns at different

scales and develop and use classifications to organise events and phenomena and

make predictions.

• As

students progress through the primary years, they become more proficient in identifying

and describing the relationships that underpin patterns, including cause and

effect.

• Students

increasingly recognise that scale plays an important role in the observation of

patterns; some patterns may only be evident at certain time and spatial scales.

What do patterns have to do with science?

·

Children naturally develop the skill of pattern

recognition but perfecting that skill requires explicit teaching for students

to understand how patterns connect mathematics and science.

·

Teachers need to provide opportunities for

students to learn how to detect patterns, how to understand patterns, how to

analyse patterns, how to use patterns and how to find new patterns.

Why teach science through the Key Idea Patterns?

•

Patterns support the development of scientific

explanations, theories, and models.

•

To support students in understanding core concepts,

patterns need to be visible and explicit.

•

To engage students in scientists’ science, we

need to engage students in using patterns as part of the scientific practices.

•

Noting patterns as a starting point for

asking scientific questions,

•

Using statistics to determine the

significance of mathematical patterns

•

Mathematical representations are needed to

recognise some patterns

•

Empirical evidence is needed to identify patterns

•

Basing arguments “on inductive

generalisations of existing patterns”